Disclaimer: Futhu is one of the millions of Rohingya refugees who have sought refuge in Bangladesh. A lengthy article in The New York Times Magazine by Sarah A. Topol recounts the following tragic story of him and his family.

During his early years in primary school, Futhu came across a captivating story about a girl who named her flowers and meticulously documented their growth in a diary. The tale was nestled within a book brought to their village in Myanmar’s Rakhine State by Futhu’s uncle, who journeyed from neighboring Bangladesh. The book presented its narrative in both English and Bengali, languages that Futhu grappled with, being the first in his extended family to attend school.

Although he excelled in Burmese and English classes, Futhu couldn’t fully comprehend the book alone, given his family’s illiteracy. Undeterred, he enlisted the help of a village trader, a frequent visitor, who read the stories aloud. With time, the book’s pages wore thin, yet Futhu persevered until he could read it independently. Inspired by the girl in the story, he began keeping a diary of his daily chores, jotting down the details in a mix of English and Burmese, as his native Rohingya lacked a written form.

The book, aside from its flowery narrative, unfolded the backdrop of World War II and the girl’s experience during a tumultuous period. Drawing parallels between that historical account and the challenges faced by his Muslim community, particularly the Rohingya, Futhu felt compelled to document the oppression they endured. He envisioned a future where people might seek to understand the plight of the Rohingya.

From a young age, Futhu understood that the government considered the Rohingya as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, despite no evidence of migration in his family history. Having endured numerous armed operations against the Rohingya since 1948, Futhu recognized the stark disparity in the rights and citizenship granted to the 135 officially recognized ethnic groups in Myanmar compared to the more than one million Rohingya who lacked such recognition.

Futhu documented the injustices he observed around him. The Rohingya faced stringent government regulations, from registering their livestock to obtaining permission for home repairs and marriages, often involving exorbitant bribes and prolonged waiting periods. Educational and career opportunities were severely restricted, with limitations on certain college majors, military service, police roles, and political participation. A two-child limit, mandatory birth control, and restrictions on medical care further compounded the challenges faced by the Rohingya. Nationality cards were systematically confiscated, and families were coerced into forced labor without compensation.

As Futhu chronicled these hardships, he sought to give voice to the silenced and shed light on the systemic oppression faced by his community, hoping that his writings would one day contribute to a broader understanding of their struggles.

Futhu found himself perplexed by the government’s relentless focus on the Rohingya community, a group deemed unwanted. Amidst the conflicting assertions of the Burmese and Bangladeshi governments regarding their identity, the Rohingya questioned their very existence on this land. Futhu, driven by a modest curiosity, embarked on documenting the story of his village, Dunse Para, in the late 1990s, seeking to unravel the roots of his community in this small patch of earth.

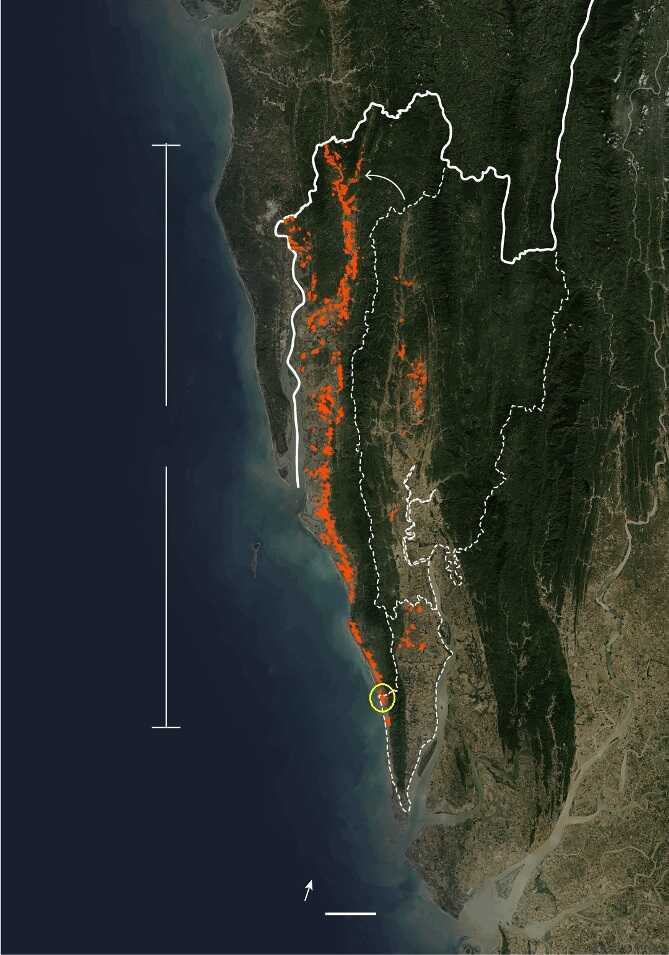

Nestled between the Bay of Bengal and the imposing Mayu Mountains, Dunse Para was a serene enclave where daily life revolved around fishing, farming, and conservative traditions. Men set out each morning in small rowboats and larger motorized vessels, while women remained at home, avoiding the scrutiny of the Burmese security services. Futhu’s inquiries into the village’s founding revealed a historical migration, starting from a hillside where buffaloes grazed to the creation of Dunse Para, comprised of four smaller villages.

Futhu meticulously documented not only the land but also the intricate family trees of the villagers. Conversations with elders unveiled surprising connections, revealing that individuals living in the same village were sometimes blood relatives unbeknownst to them. Futhu’s quest extended beyond familial ties, tracing relationships across villages and mountains. The residents initially questioned the purpose of Futhu’s writings, suspecting sorcery, but gradually recognized the value of his documentation when seeking answers about kinship and lineage.

Unaware of historical records that traced the Rohingya community back to the 18th century, Futhu’s narrative lacked the insight that outsiders had acknowledged their presence. The British colonial era, which began in 1824, unfolded without Futhu’s knowledge of its impact on Rakhine State and Burma. The open borders between Burma and India facilitated migration, with the British favoring Muslim arrivals, leading to envy and resentment among the locals. Despite this, the community fondly recalled the colonial period as a time of prosperity and peace.

In essence, Futhu’s humble endeavor to understand Dunse Para and its people unraveled a tapestry of connections, authenticity, and a deep sense of belonging to the land—a narrative that stood in stark contrast to the government’s unwarranted focus on the Rohingya.

Futhu’s grandfather recounted a chapter from World War II when Japanese forces invaded Arakan in 1942, yet the conflict spared Dunse Para. However, the untold narrative unfolded with communal tensions surfacing between the Rohingya and Rakhine, who aligned with opposing sides. The Buddhist Rakhine supported the Japanese invaders, enticed by promises of independence, while the Muslim Rohingya sided with the British colonizers, who treated them well. Futhu’s grandfather painted a grim picture of that period, describing clashes where both communities wielded knives and rocks, resulting in massacres.

As violence escalated, many Rohingya, including Futhu’s family, sought refuge in the north of the state, while the Rakhine sought safety in the south. Futhu learned of his great-grandmother’s tragic fate during those battles, unable to escape the onslaught. The family returned to Dunse Para to find their homes destroyed and their belongings gone—a pattern that would repeat in subsequent violent upheavals.

Before Burma gained independence in 1948, the country experienced anti-Indian and anti-Muslim riots, prompting many to flee. The 1950s saw promises of citizenship for those residing in Burma before British colonization, providing hope for Rohingya, like Futhu’s family. However, Gen. Ne Win’s 1962 coup dashed these aspirations, as the junta aimed to consolidate a Buddhist identity while suppressing ethnic minorities, especially Muslims. Travel restrictions were imposed on Rohingya, leading to more displacement, including Futhu’s grandfather seeking refuge in Bangladesh in 1963.

The military’s 1977 Naga Min operation intensified the plight of the Rohingya, branding them “illegal immigrants” and stripping them of citizenship. Villages were burned, mosques were destroyed, and people were herded into fenced stockades. The military raped and murdered, forcing over 200,000 Rohingya refugees into squalid camps on the Bangladeshi side of the Naf River. Forced repatriation and the 1982 Citizenship Law left the Rohingya as the world’s largest stateless population within a country.

Futhu’s personal journey began when his family, facing conscription into forced labor in 1992, joined thousands of Rohingya in a trek to Bangladesh. Unbeknownst to them, the Burmese government initiated a program to establish “model” Buddhist villages on their land, resettling Rakhine and Bamar prisoners. This marked another tragic chapter in the protracted history of displacement, discrimination, and systemic oppression faced by the Rohingya community.

In the refugee camps, Futhu’s father remained unwavering in his commitment to his son’s education. Futhu attended private classes in a makeshift shack, learning English and Burmese in a small group led by another Rohingya refugee. However, their fragile peace shattered when the family was abruptly informed of their forced return to Myanmar. Refusing meant facing violence; protests were met with beatings and death. Boarding a speedboat, the family returned to a land that had rejected them, with Futhu’s mother witnessing the remnants of their home reduced to rubble. They had to rebuild from scratch, gathering timber from the hills.

Futhu, haunted by fear, resumed his education in a Rakhine village for primary school and later boarded in a nearby Rakhine town for middle school. The persistent dread lingered, manifesting in his father’s trembling anxiety whenever the military appeared. This generational trauma permeated the community, absorbed by children through their parents’ emotions and experiences. The past, though blurred in dates and details, cast a shadow over their present, leaving them unable to envision a peaceful future. Some hesitated to build comfortable homes, while others persevered, investing in a land that continued to reject them.

Lacking funds for university, Futhu faced the harsh reality that education was a luxury. With high school completed, he initiated another journal, documenting the brutality of the government’s frontier force, NaSaKa, in the village—accounts of bribes, extortion, beatings, fines, and arrests. Despite his father’s offer to fund a small shop, Futhu aspired for more. Encouraged by a friend, he started a class teaching English and Burmese to children during the day, gathering students and securing donations for textbooks. Futhu, driven by a love for learning and teaching, adapted the Burmese curriculum into Rohingya, making education more accessible.

To better understand the world, Futhu struck deals with traders to bring him newspapers, revealing a passion for history, languages, and collecting books. His commitment to education bore fruit as his students rapidly progressed, outperforming their Rakhine counterparts in exams. The 2010 elections brought a promise of rights for votes from the Union Solidarity and Development Party, but in Dunse Para, Futhu advocated for an official school instead of individual payouts. The village chief and Futhu saw the potential for change, but convincing the community involved weeks of door-to-door persuasion. Futhu envisioned a shift in how the Rohingya measured their lives, urging them to value education over material possessions.

Not everyone shared Futhu’s vision. Concerns echoed through the community: If the Rohingya sent their children to Burmese schools, would they lose their cultural identity and values? Would they adopt habits like drinking beer, akin to the Rakhine people? Moreover, with limited opportunities for higher education or lucrative government jobs, some questioned the value of investing in their children’s education when their future seemed predetermined by systemic constraints.