After the previous part:

Futhu countered these doubts, emphasizing that education could empower the Rohingya to challenge existing norms. With an educated community, they could increase their representation in Parliament, providing resilience even if authorities targeted a few members. Futhu’s persuasive efforts, coupled with support from prominent community members, eventually led to the establishment of the first official government school in Dunse Para in 2010. However, the financial contribution from the Union Solidarity and Development Party (U.S.D.P.) fell short, prompting Futhu to form a committee to explore cost-effective construction methods.

To cut costs, they enlisted 25 volunteers instead of paid laborers and ingeniously sourced barren coconut trees from village landowners. Futhu’s resourcefulness extended to fundraising efforts, organizing a soccer tournament to finance repairs two years after the school’s founding. Despite the school’s seemingly simple initiation, the endeavor represented a monumental shift, akin to altering the course of a deep river.

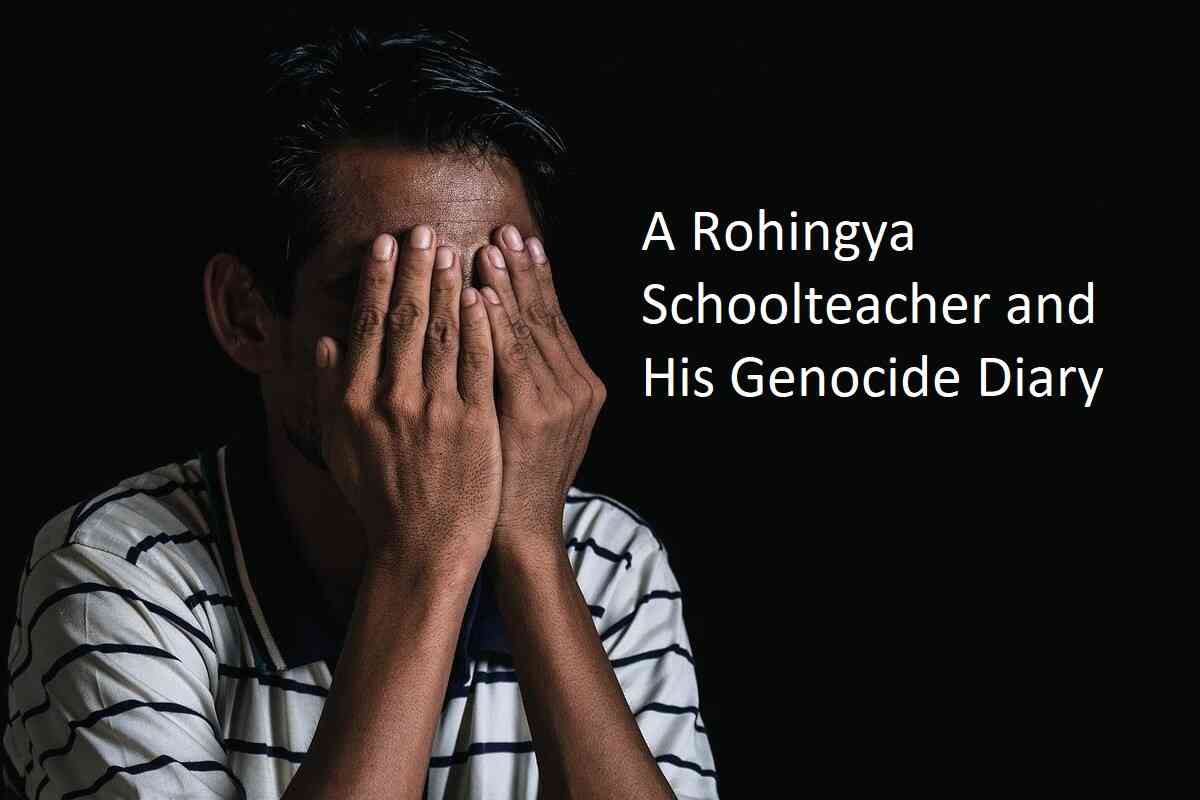

Futhu’s life took a personal turn in 2013 when he married his wife in a ceremony attended by villagers. Despite daily challenges, including their disagreements over late-night use of the kerosene lantern, Futhu continued documenting the atrocities of the NaSaKa in his coded logbook. As Futhu and his wife welcomed their own sons, his collection of over 40 diaries grew, safeguarded in a chest amidst schoolbooks and papers.

The year 2012 marked a turning point for Dunse Para. After a soccer tournament, rumors of violence against Rohingya in nearby towns reached the villagers. Communal violence ensued, resulting in the deaths of hundreds, and displaced Rohingya sought refuge in Dunse Para. The fallout reached the village, with commandeered land housing the displaced and rumors of Rohingya being confined to ghettos in Sittwe.

While the Rohingya faced escalating discrimination and a loss of rights, the international response remained muted. In 2012, President Barack Obama’s visit to Myanmar barely acknowledged the Rohingya crisis, focusing on the nation’s democratic progress. Two years later, Futhu’s exposure to the internet, particularly Facebook, revealed the alarming rise of anti-Rohingya sentiments, hate speech, and violence against Muslims in Myanmar. A group of extremist monks, known as 969 and later MaBaTha, actively propagated violence.

In 2015, Futhu embarked on a teaching career at the first official middle school in Chein Khar Li, shared by two Rohingya communities. Despite the growing tensions, his dedication remained steadfast, centered on educating the next generation amidst the challenging socio-political landscape.

On the early morning of October 9, 2016, as Futhu slept in the Chein Khar Li middle-school dormitory, the tranquility of Dunse Para was shattered by the sound of gunfire. Confused villagers sought answers, speculating about robbers, thieves, or a gang. Seeking guidance, they turned to their village chief, Ayub, a wealthy businessman with close ties to the authorities. Ayub, unaware of the situation, was summoned by the Myanmar Border Guard Police (B.G.P.) to the checkpost.

As dawn broke, the gunfire ceased, and an anxious crowd gathered near the Big Village’s main mosque. Dunse Para was gripped by fear. Ayub and his deputy chiefs were at the checkpost, surrounded by a security-service detachment. Women were confined indoors as men tried to make sense of the unfolding events.

Inside the checkpost, Ayub was confronted by the B.G.P. sector commander, who presented a captured militant allegedly involved in the violence. Ayub denied any knowledge of the individual. When shown a dead militant’s body, Ayub maintained his ignorance. The detained militant corroborated Ayub’s statement, asserting the attackers acted independently.

In the afternoon, the sector commander instructed Ayub to secretly bury the dead body in a Muslim graveyard. Ayub, accompanied by three individuals, carried out the task. Returning to the village, Ayub relayed additional rules from the authorities through town criers. The community was subjected to a curfew, restrictions on prayer calls, limits on gatherings, suspension of Quranic schools, and prohibitions on fishing and timber activities. House fences were ordered to be torn down, abruptly disrupting the villagers’ livelihoods.

Two days later, a video surfaced online, claiming responsibility for the October 9 attack. The group identified themselves as Harakah al-Yaqin, later known as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA). Led by a committee of Rohingya émigrés in Saudi Arabia, ARSA cited oppression since 2012 as the catalyst for their actions. The video detailed simultaneous strikes on B.G.P. checkposts and headquarters, resulting in casualties on both sides.

As the news spread, security services intensified their presence in Dunse Para. Officers conducted household checks, demanding family lists to identify missing members. The family complied, except for Futhu’s older brother, who had fled to Malaysia years earlier. Futhu, having been at the middle-school dormitory during the incident, was questioned by a B.G.P. commander. Despite his innocence and attempts to explain, Futhu was subjected to physical aggression, with the commander pulling his hair. The unfounded suspicion left the community in distress, with even the family’s outhouse fence kicked down by departing officers.

Following the ARSA attack, the aftermath brought a wave of interrogations to the village. Men, including the village chief’s brother, an Islamic teacher, were subjected to beatings. Ayub, the village chief himself, was eventually taken into custody, prompting his deputies to flee in fear.

Weeks later, news arrived that an international delegation would visit towns, including Dunse Para, to assess the situation. The villagers, uncertain about the delegation’s intentions, began deliberating on how to convey their plight effectively. Some proposed creating signs in English detailing their oppression, considering phrases like “RAPE, GENOCIDE, KILLING, TORTURE.” Futhu, cautious and uncertain about the approach, wondered if it was wise to raise such issues given the peaceful coexistence they had with their Rakhine neighbors.

The foreigners arrived during the harvest season, greeted by villagers eager to share their grievances. Holding signs and expecting assistance, the locals believed the delegation had come to help. Language barriers posed challenges, and Futhu, along with another teacher, stepped forward to assist in translation. Villagers shared stories of discrimination, a lack of recognition, and restrictions on their rights. The emotional plea for recognition as citizens resonated with the delegates.

However, after the meeting, the Rakhine chairman expressed anger, warning the villagers of consequences for shaming the government. Subsequently, a dozen B.G.P. trucks appeared in the village, signaling trouble. Futhu and his father hurriedly hid their diaries, anticipating trouble. Soon after, the saingom called all males over 12 years old to the Big Village.

Upon arrival, the villagers found themselves in a distressing scene. Hundreds, maybe a thousand, were seated in rows, subjected to unnatural positions, hands clasped behind their necks, heads bowed. B.G.P. officers lined the path, striking and kicking the men as they approached. Watches were confiscated and placed in a pile. Futhu, relinquishing a wedding gift, found himself singled out. His hands were tied, and he endured a brutal beating without explanation. The village witnessed the savage treatment of the educated when authorities intervened, a grim reality known to all.

When Futhu regained consciousness, he found himself bound, his body aching in pain. He had been separated from the group, and any attempt to protest or look up was met with harsh beatings from the B.G.P. officers. The officers casually smoked cigarettes, chatted, and even recorded the detainees on their mobile phones as if documenting a casual event. Futhu, struggling to stand, was ordered to a clearing where higher-ranking officials sat under betel nut trees.

One official questioned Futhu about his role in translating for the foreign delegation. Futhu, a Rohingya, faced accusations that this was not his country, and he was reminded of his ancestry from Bangladesh. Despite confirming his involvement in translation, Futhu denied knowledge of who wrote the placards. An officer, recognized from a checkpost, brutally struck Futhu in the head with a rifle, demanding information about ARSA. Futhu, maintaining his innocence, was spared further harm when the Rakhine chairman vouched for him.

As evening fell, the men were moved to a thatched house, where they were crammed together. The next morning, women and children were allowed to bring food. B.G.P. officers, however, raided homes in the Big Village, looting gold ornaments and assaulting women. Futhu’s house was not spared, and his wife confronted the officers, unsuccessfully trying to protect Futhu’s papers. Despite the chaos, Futhu’s diaries remained hidden.

The B.G.P. commander, facing a leadership vacuum, asked Futhu to take charge, which he declined, asserting his role as a teacher. Foyaz Ullah, a former leader, reluctantly assumed the position. The commander issued a warning, threatening to burn houses if the community did not comply in the future. Futhu and others were coerced into signing a statement denying any harassment.

In the aftermath, schools remained closed, leaving Futhu frustrated about the children falling behind. The community faced ongoing restrictions, with men unable to engage in fishing or timber activities. ARSA’s influence grew, and their tactics became more menacing, targeting suspected informants within the Rohingya community. Foyaz Ullah found himself caught between ARSA pressure and the military’s demand for information.

Months later, the village experienced a violent assault on August 25. Futhu, fearing for his family’s safety, navigated through the chaos to find them safe in the hills. The village, however, faced destruction, and the community sought refuge in neighboring villages, uncertain about the future. The violence continued, leaving the once-peaceful Dunse Para in turmoil.

On the early morning of Aug. 28, chaos erupted in Dunse Para and Boshora as security forces stormed in, weapons blazing. The residents, sensing imminent danger, fled for their lives. Futhu and his family, hearing explosions behind them, climbed higher into the mountains, seeking shelter under the trees. As the military entered Dunse Para, those who remained attempted to escape. Tragically, Foyaz Ullah, in his attempt to flee, was fatally shot by the very individuals he had tried to pacify in front of those he had attempted to calm.

Dunse Para and surrounding villages were engulfed in mayhem, with mothers releasing their children in the confusion, leaving elderly grandparents behind. Houses, built with their own hands, became the tragic sites of burning bodies. The brutality extended to heinous acts such as dragging and mutilating a mother’s charred body. From the vantage point of the hills, Futhu witnessed the destruction of his world. Multiple villages below were consumed by red flames and black smoke, obliterating the school he had built, the books he had collected, and the knowledge he had painstakingly chronicled in diaries.

The violence across Rakhine State had erupted following 30 simultaneous attacks by ARSA on checkposts on Aug. 25. However, the government’s response did not distinguish between civilians and militants, unleashing a relentless crackdown that had been in preparation for months. The military, influenced by anti-Rohingya propaganda on Facebook, perpetrated massacres resulting in the deaths of at least 10,000 men, women, and children through various gruesome means.

In the aftermath, confusion and rumors permeated the hills, with families constantly changing direction based on the destruction they encountered. The hills became a landscape of despair, with bodies, both alive and dead, scattered everywhere. Futhu, despite the urge to search for his diaries, was prohibited by his father, who emphasized the risk of returning to their village.

Fleeing to Bangladesh, Futhu and his family joined the 700,000 Rohingya in one of the largest refugee exodus in recent history. Settling along a main highway initially, they were later commanded by the Bangladeshi military to move into the dense jungle. The refugee settlement became the most congested on Earth, with monsoons causing landslides and endangering both refugees and wildlife.

Amid the chaos, Futhu, almost a year after the tragedy, documented the events in a new diary. His attempt to create a timeline revealed the challenge of organizing memories tainted by death, flames, and violence. Realizing the need for another document, he compiled a “List of Died” in English, memorializing the 12 lives lost in his village.

A year later, Futhu shared his story with me (original author Sarah A. Topol) near a bridge in the camps, revealing the misery and challenges faced by the Rohingya. Despite the horrors, Futhu maintained a belief that change was possible through perseverance, as he had no other choice but to live each day on borrowed time.

Living in the camps offered both respite and challenges compared to life in Myanmar. While the threat of being killed diminished, restrictions on leaving the camps and the need for permission to access proper medical care underscored the external control over their lives. Negotiations for repatriation between Myanmar and Bangladesh continued, with many Rohingya demanding official ethnic recognition before agreeing to return. Meanwhile, the presence of ARSA in the camps and ongoing executions created an atmosphere of fear, complicating the already delicate situation. The uncertainty of the Rohingya’s future hung in the balance as international organizations attempted to mediate.

In Bangladesh, Rohingya refugees face severe educational challenges as they are not allowed to enroll in government schools. UNICEF’s “child-friendly spaces” aimed at providing learning opportunities turned out to be places for play and drawing, with aid agencies establishing “learning centers” lacking a structured curriculum. Private tutoring schools offered only basic math and language instruction, leaving a significant gap in subjects like history and science necessary for comprehensive education. Futhu, a refugee, attended such schools but found them insufficient.

Despite daily survival, Futhu, once an avid diarist and teacher, ceased documenting his experiences and teaching due to the crowded and humid conditions in the camps. In the absence of a conducive environment, his nightly chronicles were replaced by sporadic notes on his cellphone. Futhu’s resilience was evident as he volunteered for the World Food Program and rose to manage an aid-distribution site. However, uncertainties about the future and the desire to return to his homeland lingered.

As Futhu reflected on the possibility of returning to Dunse Para, the news of the Burmese government constructing a model village on the once-fertile land stirred mixed emotions. The traumatic events of Oct. 9 and Aug. 25 replayed in his mind, making the prospect of losing their land even more painful. In moments of reflection, Futhu grappled with the hardship he endured, questioning the purpose of living such a life. His anguish culminated one night as he questioned the value of his efforts and the hardships faced by his family.

During our conversations, Futhu, typically optimistic and purposeful, posed a single question: What did I think would happen to the Rohingya? Unable to predict the future, I turned the question back to him, asking about his thoughts on returning to Dunse Para. His responses fluctuated between a desire to return with rights and a willingness to face an uncertain fate in the sea.

As I shared information about the Burmese government’s plans for a model village, Futhu expressed skepticism, unwilling to accept the idea of being displaced from their land. The haunting dreams of his deceased father, buried in the camp graveyard far from their homeland, added to the emotional burden. Futhu grappled with the inevitability of death but struggled to forget the hardships he endured.

In a poignant moment one evening, Futhu, surrounded by family and neighbors, questioned the purpose of living a life filled with hardship. He expressed disillusionment with having children, contemplating the usefulness of his parents’ sacrifices for his education. The emotional weight of his experiences overwhelmed him as he considered letting go of everything.

As I departed, I offered Futhu a notebook, hoping he might find inspiration to resume documenting his thoughts. The farewell was heavy, and Futhu shared his certainty that returning to Myanmar would result in their deaths.

In the subsequent weeks, our communication continued over WhatsApp, with Futhu sharing updates on his renewed diary entries, dreams of saving money for a computer, and involvement in tree-planting projects to prevent landslides. A new initiative emerged as he collaborated with community leaders to open a school teaching Burmese, English, and math to 1,000 students. Despite financial constraints, they completed the school in December, reflecting Futhu’s determination to provide education in the face of adversity.

Through messages, Futhu expressed ongoing concerns about his diaries and inquired about the reception of this article in America. He sought a copy of the magazine, emphasizing its importance for the future. Despite the challenges, Futhu’s resilience and commitment to education and community development remained unwavering.